Molly - Picnics & Portals

I've established that I love going to movies. When presented with an opportunity to have a night out alone that's almost always what I will choose to do. Recently, the local nonprofit theater hosted a showing of Picnic at Hanging Rock, Peter Weir's 1975 adaptation of Joan Lindsay's novel. I've read the novel, seen bits of the film here and there, and watched the recent miniseries starring Natalie Dormer, so I am familiar with the story.

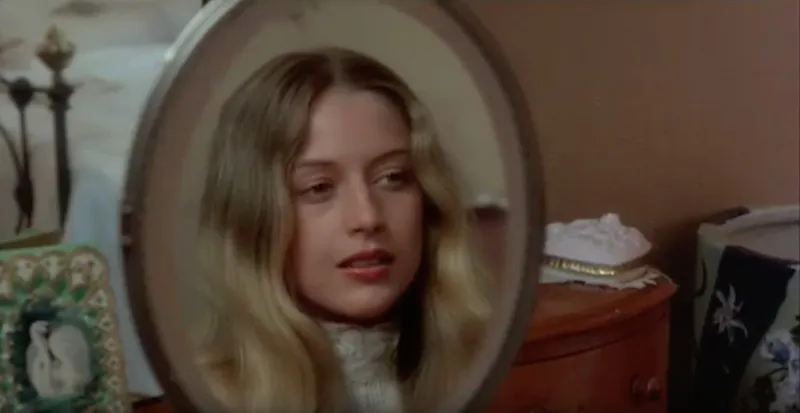

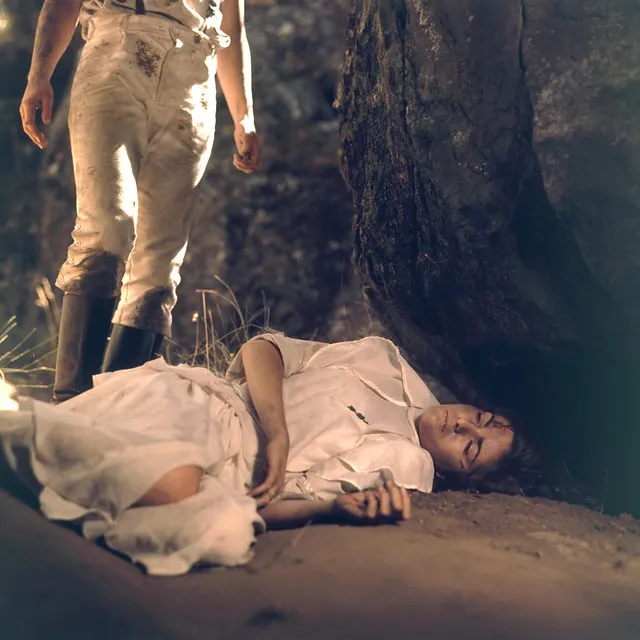

In short: On Valentine's Day 1900, the students of the Appleyard College for Young Ladies make an excursion to Hanging Rock, a geological formation in Victoria, Australia. During the picnic, three senior girls - coquettish Irma, radiant leader Miranda, and self-possessed math nerd Marion - climb the rock and disappear. One of their teachers and chaperones, Greta McCraw, later follows and vanishes as well. Some days later Irma is found unconscious with no memory of what transpired. No trace of the others is found, and we watch as the survivors cope and the college administration breaks down. I wasn't prepared for how gripping the movie is, especially on the big screen.

It may be one of the best movies I've ever seen. Picnic at Hanging Rock is not toppling any of my favorite films, which I will watch in any format and carry the glow of with me anywhere. Maybe it's more accurate to say it is one of the best movies at being a movie I've ever seen; an indestructible argument for the amalgamated arts of cinema. It transports you into its dreamscape immediately and holds you to the end. Lindsay's novel is very good and I wholeheartedly recommend it. The miniseries has some great performances and does interesting things with the book's gestures towards science fiction, but I think it's ultimately a disservice to the relatively spare story to give it a bloated runtime and character backstories. Part of the unsettling effect of the movie is the sense that everything and everyone not native to its rural Australian setting has been teleported or dropped, prefab and unceremoniously, into the tableaux.

While Picnic at Hanging Rock is by no means an obscure film, I would guess most people's main experience with Peter Weir's work is The Dead Poets' Society or Master and Commander. That includes me! Nobody is going to convince me to stop liking Dead Poets Society even though I know it's a little overly sentimental. There's something P.A. Works about it. Picnic at Hanging Rock is Madhouse. Maybe even Science Saru. Whatever it is, it gets the Noitamina block.

But get past the initial "art movie" vs. "crowd pleaser" boxes and I think these films have some interesting things in common. Weir seems compelled by impenetrable, closed-gender spaces. Dead Poets Society inspires gender envy in me, on a short list with teen boys and their loping running gaits and being a Jesuit. Furthermore it's not surprising that his portrayals of male spaces are more legible, more entertaining, than the chthonic murkiness of Picnic at Hanging Rock's feminine world.

It's an inverse of the movie it greatly inspired, Sofia Coppola's The Virgin Suicides. Where Joan Lindsay is a woman having her work adapted by a man, Coppola's film is based on the novel by Jeffrey Eugenides. I love both versions of The Virgin Suicides but they do feel completely different. Reading the book, narrated by neighborhood boys in a collective first person, I could feel their frustration at only getting glimpses of the feminine mystery that captivated them. In Picnic at Hanging Rock, the girls pass a young Englishman, Michael, and his valet, Bertie, on their way to their fateful hike. The boys watch the girls and remark both respectfully and not on their beauty, but they don't move as the girls, one by one, cross a small creek. Miranda, the most beautiful and elusive, hesitates before she executes an elegant hop. We see this through Michael's eyes as she goes where he knows he cannot follow - how a simple feminine gesture, a glimpse of stocking and calf - can undo a man. The entire reading experience of The Virgin Suicides is like that scene. In Coppola's film, we are close to the girls and feel the boys' intrusiveness and out-of-their-depthness acutely, even though the boys' narration is still in the script, a delicate trinket wrapped in an old t-shirt.

**

The "portal fantasy" subgenre contains stories where characters enter or are pulled into a fantastical world that remains separate from our own. The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe and The Wizard of Oz are two towering examples of portal fantasy, but it also includes many contemporary isekai anime and manga. Usually, these are also coming-of-age stories in which the adventure within the fantasy world teaches young characters something they can take back with them to their mundane, but now changed, lives. Isekai stories in the recent past have messed with this formula by often making the crossover permanent, or a reincarnation fantasy. Furthermore (and worse), there has been a subsubgenre of these that feature disaffected, genre-savvy protagonists whose acclimation or indeed accelerated flourishing in the fantasy world are a nihilistic flipside to traditional portal fantasy. These characters are rewarded not for conquering something in themselves on a fantastical adventure, but for logging countless hours checking out of their lives.

Without going full "is a ravioli a sandwich" with it, I have a liberal view of what constitutes portal fantasy. For me it includes what I call "boy walks into the forest and comes out forever changed" stories. The greatest of these is Alain Fournier's Le Grand Meaulnes, or The Lost Estate in English. It is Fournier's only novel, published in 1913. He was killed in WWI only a year later at the age of 27. The book is narrated by Francois, the unassuming teenage son of a school director in rural France. He is captivated by Augustin Meaulnes, a slightly older boy with a bold personality. One night Meulnes runs away into the forest and happens upon a mysterious costume ball at a grand but dilapidated chateau. He meets and falls in love with Yvonne, the ethereal daughter of the estate. Meulnes returns home, tells everyone about his fantastical night, and vows to find the estate, and Yvonne, again. He enlists Francois, but they are unable to find any evidence of the place or the girl.

To greatly condense the story, a few years pass and Francois manages to find Yvonne and her family. The estate turns out to have been less grand and closer than the boys had imagined. He reunites Meulnes and Yvonne, who marry, but Meulnes soon abandons his bride. Francois does his best to keep a languishing Yvonne company, but she dies shortly after giving birth to a daughter. Meaulnes eventually returns to claim his child. The boys are now still only young adults.

Le Grand Meaulnes is a book of overwhelming beauty and sadness. It's hard to think of something that so well captures the pain of leaving childhood and aging. It is a tragic version of a portal fantasy not only because the portal was, in fact, the real world, but because Meulnes chased the fantasy of the experience at the expense of growing into a responsible man. The spectre that haunted the boys and gave their adolescence a great narrative quest was a real girl, and her suitor was ill-equipped to face her outside of fairyland.

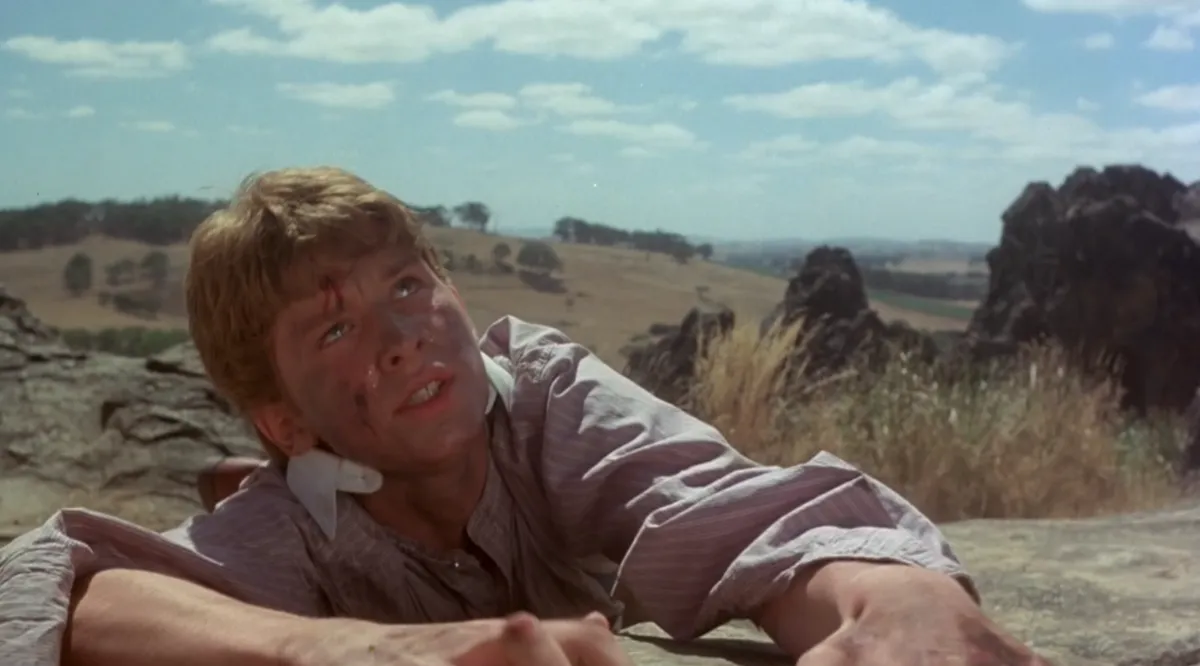

In Picnic at Hanging Rock Michael reminds me a little of Meulnes in his obsession, a little of Francois in his gentle bearing, but he doesn't quite fit the role of actor, seeker, or hero in the same way. Even if he sees Miranda as the lost fairy princess, it is she and the girls who are wandering into the forest, not him. When he later goes back to the rock to search for the girls himself, there is none of the languid wandering and soporific heat of Miranda, Irma, and Marion's climb. He's assaulted by the elements and blinded by the shadeless glare, almost as if the rock itself is rejecting him.

**

I would be remiss not to mention Tana French's In the Woods. French's debut and introduction to her "Dublin Murder Squad" series is controversial and polarizing. Like Lindsay's novel, it is a mystery that breaks the social contract of the genre. Rob, the narrator, is a self-styled noirish detective in Dublin when the murder of a preteen girl brings back the past he's fought to erase. As a child, Rob was one of three children who went into the woods near their housing estate one night. Only Rob was found, with blood in his sneakers and no trace of his friends. Since then Rob has changed his name, trained himself out of his native Irish accent, and distanced himself as much as possible from that unsolved case. By the end of the book, Rob's facade is in shambles but he, and us, are no closer to knowing what happened that night in his childhood.

I went looking for any mention of Picnic at Hanging Rock in interviews with Tana French and was a little surprised to find nothing. At this point, Lindsay's novel is read by most as literary fiction. I do remember reading a statement from French once that she thinks readers would have been more accepting of Rob's mystery remaining unsolved if her book had been marketed as literary, not mystery/detective fiction. This is very funny to me as a "literary" person who reads a lot of mystery. Famously, I like wanting to know what's going to happen.

The shared DNA goes far beyond leaving a mystery unsolved. Both crimes in In the Woods happen near a housing subdivision, the first being in the titular woods and the second at the site of an archaeological dig happening in the area. Like Appleyard college and all its Victorian rigidity imported to a hostile landscape, the blandly middle class estate is in conflict with the forest and the knowledge of buried pagan history. The modern construction disturbs the old and the untameable, which in turn takes, accepts, and rejects those who stray into its heart. In adulthood, Rob has come to think of himself not as the lucky survivor, but an outcast:

There was a time when I believed I was the redeemed one, the boy borne safely home on the ebb of whatever freak tide carried Peter and Jamie away. Not any more.

Sometimes I think about the sly, flickering line that separates being spared from being rejected. Sometimes I think of the ancient gods who demanded that their sacrifices be fearless and without blemish, and I wonder whether, whoever or whatever took Peter and Jamie away, it decided I wasn't good enough.

Rob has a bit of both Irma and Michael in him. Relatedly, if I have one...not even a complaint, but reason to read the book after seeing the movie...about Picnic at Hanging Rock, it's that those two characters' stories are very interesting in a way the movie doesn't adapt. Like Marion, Miranda, or even Miss McCraw, Irma is elegant and self-possessed, though takes life a little less seriously. She is less in awe of the rock, and she speaks no cryptic phrases like her companions. In the book's excised (later published) final chapter, Lindsay explains that after the girls go through a portal in space-time, it closes in front of Irma as she beats her fist against the stone. In the movie, she is still found practically uninjured save for cuts on her hands, a remnant of Lindsay's vision for her fate.

Although the characters are lightly sketched in the film, we get the sense that Irma is wealthier and in general the most set up to thrive in Victorian society, at least by superficial criteria. In the book, we know that she is. She is an heiress to a mining fortune, adding another element to her rejection by the rock. More so than the other girls, she is a symbol of England's intrusion on Australia's natural resources ("waiting a million years...just for us!"). Brainy and serious Marion is facing a future where society does not value the qualities she nurtures in herself. Miss McCraw, full of "masculine intelligence," is already an example of the lonely life Marion might find for herself. Miranda may be a goddess (a Botticelli angel, as the kind and lovely Mademoiselle de Poitiers observes) but her beauty is more at one with the natural world she so reveres. It's easy to imagine her getting married off and isolated from these wild and spiritual things that are written off as girlish pursuits. Can a Botticelli angel ever be relegated to "the angel of the house"?

Irma is found unconscious by Bertie after Michael's search fails, though Irma believes Michael to be her savior. Convalescing at the home of Michael's aunt and uncle, she immediately seems part of their world. We, and I think she, understand on a gut level that she was not allowed to follow her friends. In the book, the adults conspire to betroth Irma and Michael. Irma develops feelings for him though she senses he doesn't return them, but everyone goes along with it for a while. Michael eventually leaves before anyone can stop him. Michael, like Irma, is superficially poised for success in polite society. He never stops dreaming of Miranda, and with her, I feel, an adventurous and freer life than might be actually available to him.

I find Michael and Irma being thrown together by circumstance and the restrictive nature of their roles in life to be one of the best parts of the book. And like Newland Archer's love for Ellen Olenska in The Age of Innocence I believe that Michael wants to be Miranda as much or more than he genuinely loves her romantically or sexually. In fact, book Michael seems pretty gay - something that comes through in the movie with his friendship with Bertie, and especially his role as a typical damsel when Bertie rescues him. For Newland Archer and Michael, the fantasy of a woman ignoring conventions can be one of unbridled freedom and creativity, because this fantasy ignores that such women in their eras would have born the weight of shame rather than the pressure of acceptance.

Irma...also kind of gay actually! The relationships at Appleyard college follow the "Class S" model: a genre of Japanese literature where queer love between young women is represented through poetry, botanical motifs, and yearning, often between a mentor figure and younger woman. Orphan Sara's love for Miranda is an obvious example, but Irma has a special affection for Mlle. de Poitiers. Leaving school would represent an end to these innocent but intense attachments in favor of an uptight Victorian marriage. By the end of both the movie and book, it seems more and more that many of the survivors are the true tragic figures, not the missing girls.

To become self-parody in my inability to stop brining up The Age of Innocence, I have always thought that Newland Archer's story is almost a thought experiment responding to heroines like Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, Edna Pontellier, or even Wharton's own Lily Bart. In these stories, romantic heroines step outside society and off a ledge, leaving them in a place where suicide seems the only option. So what if that story were about a man instead? Newland's achingly melancholy fate, my favorite ending in literature, is only possible because of the choices he had as a man.

Likewise in my loosely defined portal fantasies like Le Grand Meaulnes and In the Woods, the male protagonists are mostly miserable but they did have the opportunity to forge a life and remake themselves even if they sucked at it. Emerging from the forest changed is a kneecapped experience if you lack the full agency to act on the lessons learned. In a dreamlike, but ultimately grounded-in-reality story like The Virgin Suicides, death is again the only true escape from an oppressed existence. But in Picnic at Hanging Rock there's almost an optimistic sense of these girls who knew they were on the brink of a dimmer, blander life being accepted by the portal.

The physical differences in these stories are also significant. A forest may be as awe-inspiring and savage as Hanging Rock, but it is also secret and dark. "Entering" and "leaving" make sense as things you can do to it. Hanging Rock explodes out of the landscape, visible for miles. It is hard to comprehend in its entirety but it is a shape with boundaries. There is only so much rock to get lost on, only short ways you can go without being able to see the land and ground below you. Like Appleyard College it looks dropped wholesale onto the earth, but from an ancient, alien place.

As Mark Fisher wrote on his blessedly preserved Website:

The rock is spatially as well as temporally anomalous. It can only be seen in fragments, its labyrinthine spaces as intensively treacherous as those of another alien picnic site, Tarkovsky's Zone. The rock is effectively navigable only by the attaining of a delirium state

Adolescent girls occupy a precarious place in the world and on life's timeline. It's as if this liminal stage is a natural resource everyone is fighting to control, whose natural and rightful owners barely understand it themselves. Those on the outside (Michael, the narrators of The Virgin Suicides, etc.) are obsessed by the other. Those of us on the inside can't stop revisiting this time and turning it over and over, looking for some kind of closure? recapturing? that never quite comes. Most of us have long been aware of other people looking at us, call this the "looking glass self" or "objectification consciousness," or any of the many ways people have tried to articulate the knowledge of being observed. The watchful eye manifests in variously benign and malevolent ways: being given special attention, prized, and valued for beauty, or being preyed on for the same thing. In an earlier post I wrote, "Some other day maybe I'll get into the idea that girls are overvalued (derogatory) and boys are undervalued (derogatory)." I am not about to do that, exactly, but this idea courses through the world of Picnic at Hanging Rock.

The girls are monitored constantly. It's in the way they are advised to only remove their gloves once their mostly covered wagon passes through the nearest town, even though it's a blisteringly hot day. The disappearance makes global news, with people traveling to see the Rock for themselves. A nosy reporter even sneaks onto the campus to photograph the Appleyard students. Sara, an orphan whose place at the College is insecure at best, is nitpicked and even physically punished over her bad posture. She loves and admires Miranda, the only person aside from Mlle. de Poitiers to show her kindness. Before the fateful excursion, in which Sara is not even included, Miranda tells her "you must learn to love someone else." Miranda's voice lacks conviction, though. She knows as well as anyone, including Sara herself, that the world is not prepared to take care of her. The disappearance of some of Appleyard's most "high value" girls has a trickle down effect of more cruelty and negligence towards its most "low value" girl. Mrs. Appleyard can tolerate Sara, albeit begrudgingly and with harsh discipline, when girls like Miranda or Irma are representing her school. Without them, she can no longer afford nor pretend to care about the orphan.

At the end of the film, Mrs. Appleyard tells Sara she will be returned to the orphanage since her school fees have not been paid by her absentee guardian. The next morning, Sara's body is found in the school greenhouse. Some people think she was pushed by Mrs. Appleyard. I think it was suicide, and in Sara's mind, the only way she could join Miranda. When the gardener runs to tell Mrs. Appleyard, she is already sitting in her office dressed in mourning apparel, her things in suitcases around her. The film ends on text telling us that Mrs. Appleyard's body was found at the base of Hanging Rock shortly after. Mrs. Appleyard's identity hinges on her brittle but tenacious adherence to Victorian etiquette. She is a widow with a drinking problem, and without the proof of "turning out" fine young ladies, she has nothing. Her disdain for Sara seems to be a hatred of recognition. They are both utterly dependent on other people, specifically more highly valued women. They cannot even credibly imagine freedom or rebellion for themselves - Mrs. Appleyard has never tried, and Sara's spirit has long been broken - and so they die real, mundane deaths instead of being spirited away. The portal is only open for a short season of life, and even then you must be brave enough to go through it.

Lindsay's final chapter, with the hole in space-time, floating corsets, and a talking lizard, has been available to read since 1987. I get the sense many readers and film fans don't accept it as the ending, or the ending rather. And sure, I think Evangelion's best ending is the original series and I am hesitant to come down firmly that End of Evangelion is what "really happened" or whatever. People seem attached to the book and film's true crimeish, unsolved mystery angle. There is a collective ownership over girlhood in society - another facet of being overvalued. We feel entitled to watch it and comment on it. An unexplained but still mundane disappearance lets us feel like there's still something to watch. Michael's dreams of Miranda or the Virgin Suicides boys' adult retellings are ways of keeping a tether to that evanescent brush with femininity.

"Everything begins and ends at the exactly right time and place." I can imagine the "everything" in Miranda's final spoken line including the experience of adolescence itself. It's harder to imagine any real person having the sense that their own youth ended in a satisfying, exactly right way. Closure is usually fake, but maybe it exists on the other side of a rift in space.

This seems as right a time and place as any to end this post. Like Picnic at Hanging Rock, and the rock itself, I think it's impossible to understand and see everything important about it all at once.