Molly: Floating Weeds

When I sit down to write I always ask myself "how can I make this about the Age of Innocence?" My favorite book and movie are on my mind so often that their being the in-road to how I approach such a diversity of other topics is unforced. It's usually my favorite line, which comes near the end of the story:

It was the room in which most of the real things of his life had happened... Looking about him, he honored his own past, and mourned for it. After all, there was good in the old ways.

This line is what's going through my head in a gender swapped version of the "I bet he's thinking about other girls" meme. It is one of the most haunting passages in literature to me. There are at least three ways to interpret why it's tragic. Newland Archer is reflecting on his life with resigned melancholy. It's sad perhaps because the life contained in this room strikes him as small. Or maybe it's because the things that changed and molded him the most are not in this room. The most important things are, in a sense, not real.

It's sad for a simpler reason: some people have no such rooms. Many of the rooms where the real things in my life have happened are gone or otherwise inaccessible now. It's not that those parts of myself are lost, but it makes them precarious. Without the physical space to reiterate meaning, I have had to carry the things around like a box that never gets fully unpacked. If you've ever moved a lot or are in some otherwise transient state, you know the pain of walking into the home of someone who is obviously, decadently settled.

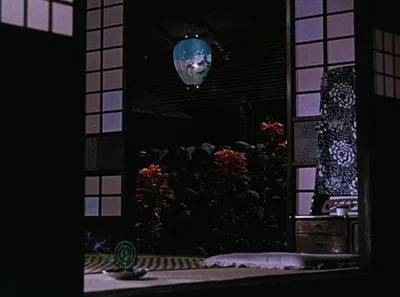

Yasujiro Ozu's 1959 film Floating Weeds is a film about rooms and the people who pass through them. Ozu's signature "tatami shot," where the camera is placed near the floor, as if the viewer were sitting on a tatami mat, works beautifully to let interiors speak for themselves. Shots of objects or empty rooms are used as transitions between actors' scenes. It feels generous, giving us moments of quiet contemplation about how these places bear the marks of the lives lived in them - or in some cases, how even the most emotionally charged experiences leave our surroundings unchanged.

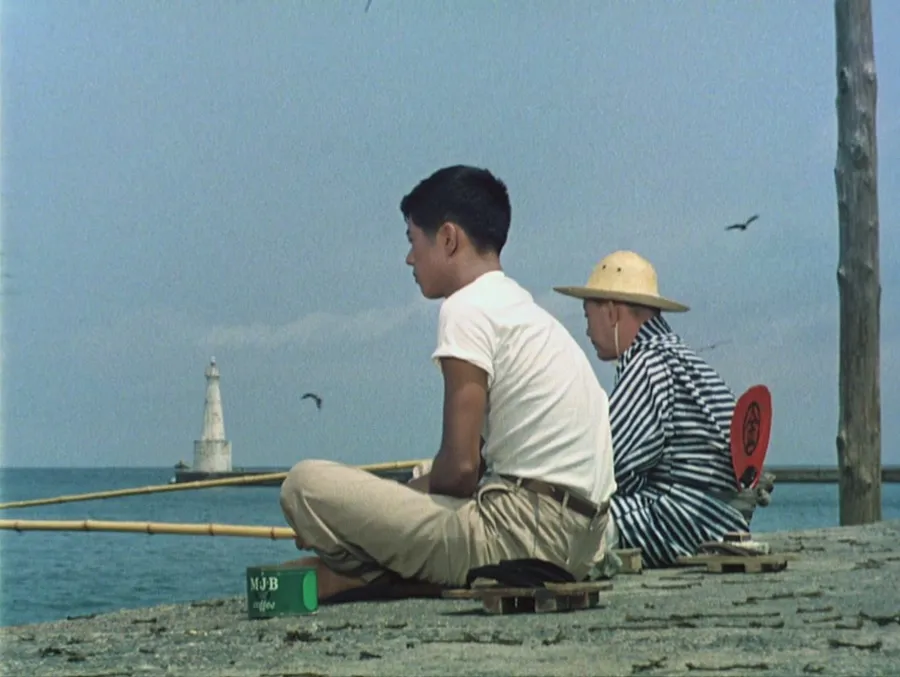

Floating Weeds tells the story of Komajuro, the lead actor and owner of a traveling theater troupe, and his fateful stay in a sleepy seaside village. Komajuro is concealing his true motives for stopping in this town, and the troupe is a little confused as to why they would land somewhere so unlucrative. In the opening scenes of the film, the troupe marches through the village upon arrival, trying to drum up some fanfare and excitement. The townsfolk, for their part, don't seem inspired enough to beat the inertia of their humid summer languishing.

But this is the place where Komajuro's former mistress, Oyoshi, lives with her teenage son Kiyoshi. Komajuro is Kiyoshi's father, but as his parents have chosen to keep this a secret, he's just an "uncle." I've often joked with Paul about how in my attraction to older men, I'm drawn to wildcard uncle energy over "daddy." The implications of a dad with uncle energy are troubling, though. A dad has obligations to his family. An uncle can blow in for the fun parts, never staying long enough for his own family to lose the sheen of vacation.

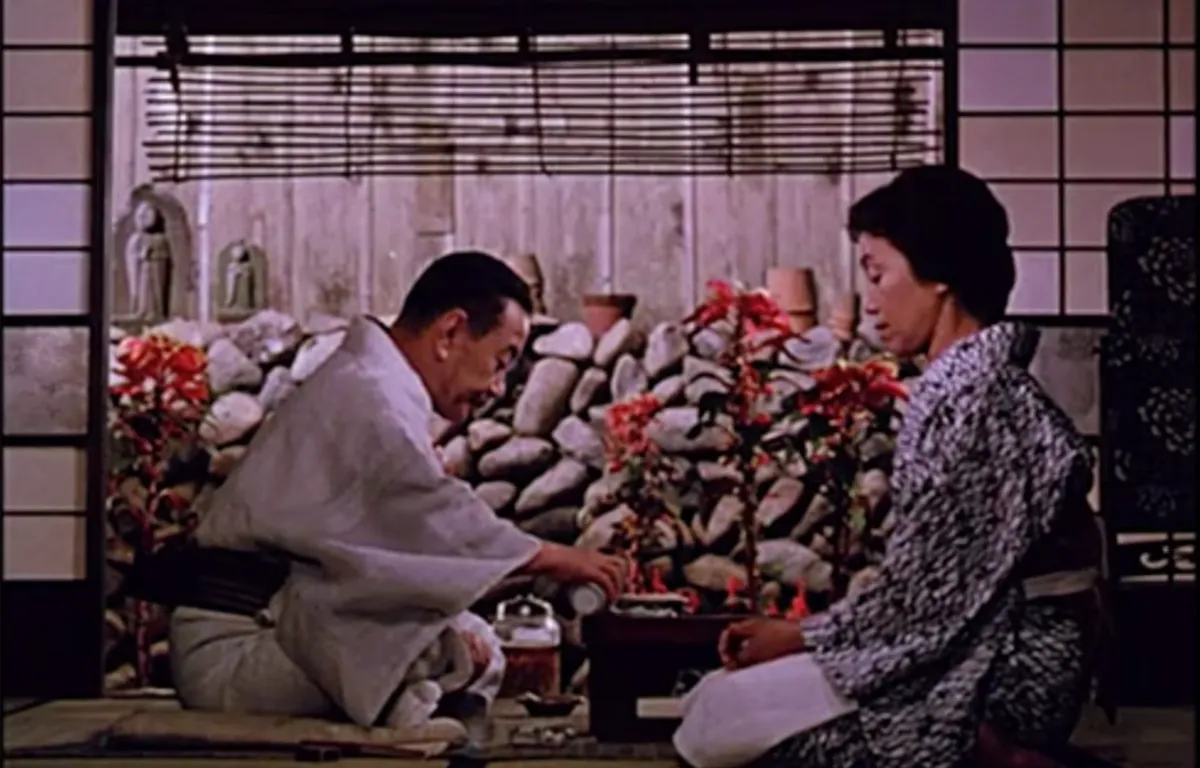

Komajuro is a fascinating protagonist. He is not unsympathetic, but liking him is an uphill battle. His desire to be involved in his son's life and have some semblance of a homebase is only human. He is also selfish, tempermental, and cruel to the women in his life. Most of the time, he does not act in a way that is worthy of Oyoshi's welcome and graceful resignation to his flighty presence in her life. There are a few touching scenes that offer a vision of what life could be if Komajuro settled down. Oyoshi sits at the bottom of the stairs listening to a sound she has so seldom gotten to hear: her son chatting and joking with his father. Later, when Kiyoshi comes home after his own crisis, he stands between his parents, who are sitting across from each other as if they had been sharing that routine for decades. But our leading man is someone who is constitutionally unable to accept these good things.

When Komajuro is in Oyoshi's space, he sinks into his surroundings as if they had always been his home. Oyoshi doesn't need to guess his preferences or ask how to make him comfortable. He has his seat, his drink. When Komajuro is absent, the tatami mat overlooking Oyoshi's garden looks pristine and undisturbed. This is all some real unbearable lightness of being stuff. I can feel the emotional weight of his leaving and how he easily completed the tableau. I can feel how heavy his absence is to Oyoshi, getting a taste of what it looks like to have a familiar person sharing his days with her. But everything about the room without him is perfect and considered. Komajuro spends the duration of Floating Weeds dropping emotional anvils on everyone around him but his literal, physical presense or absence leaves barely a trace. It would be nice for Oyoshi to finally have her family whole, but she will be fine without him.

Things spiral out of control for Komajuro when his girlfriend and fellow troupe member, Sumiko, catches on to Oyoshi being his old flame. Not only does she quickly figure out that Kiyoshi is his son, but she enlists Kayo, the troupe's beautiful ingenue, to seduce the young man as an act of petty revenge for Komajuro's lies of omission.

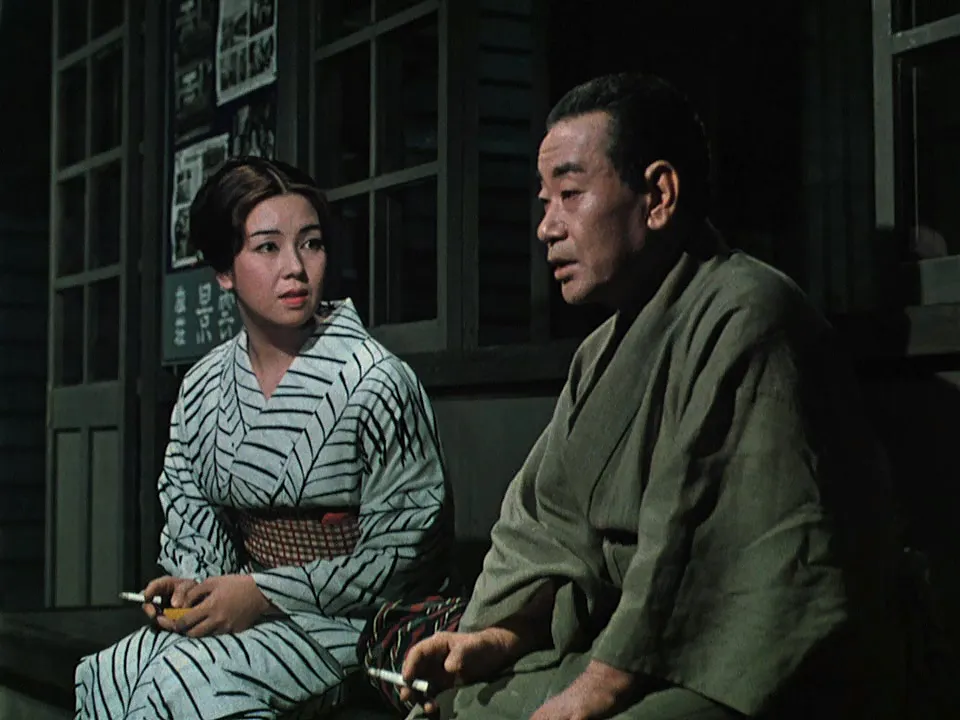

Sumiko is a great foil to Oyoshi: vain, harsh, and fiery. Though Sumiko is younger, the women's looks are a clever contrast, too. You can see beauty in Oyoshi's natural aging, and a shade of the young woman Komajuro loved. Sumiko is not quite young, not quite solidly middle-aged - an awful twilight space for women. She is trying, with varying success, to keep a vise grip on her wiles. And she is acting insane - crashing out as the kids say - but I feel for her too. Who knows if Komajuro hasn't had dalliances with other women in other towns? And Sumiko's position is frightenly precarious. As Komajuro reminds her in anger, she was a prostitute before he found her and brought her into the troupe. Without his protection, she is at sea.

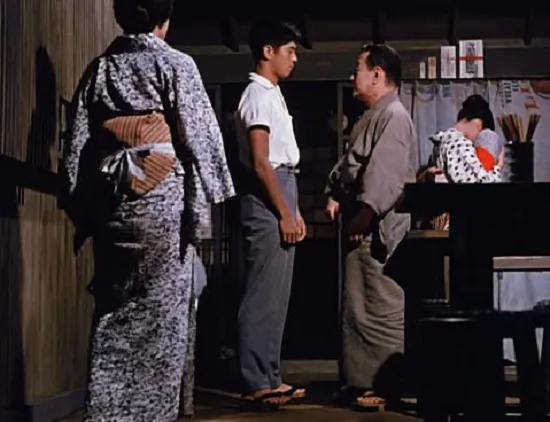

Kayo takes the bribe to seduce Kiyoshi, showing up at the post office where he works. Their physical relationsip is mostly offscreen, but we can feel Kiyoshi's adolescent horror and excitement at the appearance of the beautiful, worldly Kayo. There is a sense of helplessness and inevitability to it all, especially on Kiyoshi's part. Kayo fesses up to the scheme when she realizes her feelings for Kiyoshi are genuine. But so are his, and he doesn't care. They spend the night together at an inn, and Kayo again tries to break things off, knowing how a relationship with an itinerant actress could damage his reputation, not to mention his plans to go to college.

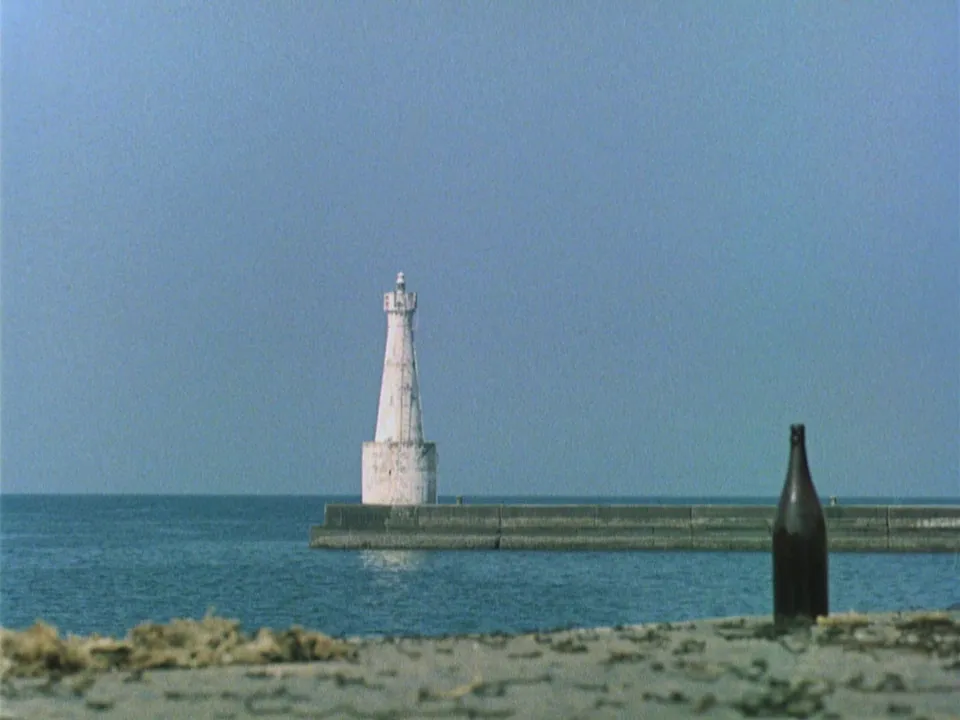

The mirror images of Kayo and Kiyoshi at the inn and Komajuro and Oyoshi in her home are striking. At first glance it may seem like a dichotomy: the temporary vs. the permanent, the salacious vs. the domestic. Even the contrast of sake poured from Oyoshi's simple dishes with the ramune bottles suggests the steady and long-term vs. the disposable and fleeting. But they are both rooms where real things happened, and where the creators of those real things can't remain. Through his cowardice and dishonesty, Komajuro has contributed to the pain of his own life being repeated in the next generation. Kayo already sees her relationship with Kiyoshi as something she must abandon for his wellfare. If, heaven forbid, she became pregnant because of their night together, this conundrum could result in another separated family.

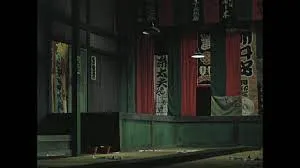

In the background of Komajuro's personal drama, the theater troupe has failed to make enough money in the village. Their kabuki style performances aren't popular, and the troupe's manager has abandoned them. The theater is empty, and discarded show flyers are the only proof the troupe was ever there. In a final meeting with his fellow actors, Komajuro apologizes and asks the group what they will do. A few of them have leads on jobs, some with relatives. It struck me that their alternate prospects are more "real" than their lives on the road with Komajuro, and that he feels his own insignificance as a figure that can so easily disappear not only from a given audience's lives, but those of his own peers.

Everything comes to a head when Kiyoshi returns home, Kayo in tow. Kiyoshi insists on bringing her home, ignoring her protests of damage to his future. Komajuro loses his temper at Kayo, at Kiyoshi, at everyone. He grasps at someone or something other than himself to blame for the unraveling. His anger at Kayo is, in a way, just perpetuating his own inability to trust his son with the facts of his own life. The truth - which Kiyoshi suspected anyway - comes out. There is the irony of this strife happening because of of a secret kept, onstensibly, to shield Kiyoshi from shame. It's obvious that being honest from the beginning would have done less harm. Komajuro runs away from a sad-but-not-surprised Oyoshi. In the wake of his destruction he does do the good thing of asking Oyoshi to take care of Kayo. By forcing her into a legitimate home and family structure, he may have ensured her future and saved Kiyoshi from a repetition of his own sorrows. He has made this home he can't bring himself to stay in a room for Kayo and Kiyoshi to fill with real things.

In the end, Komajuro sits alone in one of life's ultimate transitory rooms: a train station. He goes to light a cigarette and finds he's missing his lighter. Sumiko, also alone in the station, offers hers and Komajuro eventually relents to the gesture. They agree to travel together and seek acting prospects. "To give it another go," as Komajuro says. The sadness, a wistfulness rather than a tragedy, of this ending feels right. Who else could he end up with but the woman he mentored in his restless lifestyle? Sumiko pours Komajuro sake on the train, a fellow "low status" performer taking the place of Oyoshi pouring sake in her sitting room. The final shot of Floating Weeds is the train retreating into the night. Outwardly, the village isn't very different from how the troupe found it earlier that summer. But unlike the plants the film takes its title from, life-changing things have happened beneath the surface.